Underground Railroad gives up its secrets

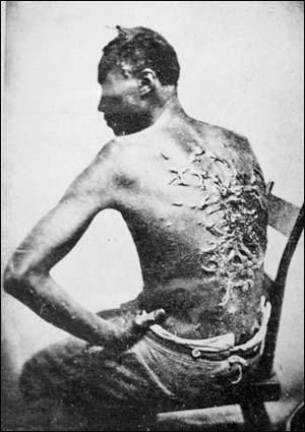

Chester and Goshen were important stops on the way to freedom, By Ginny Privitar “Have we an Under-Ground Railroad in Orange County?” An Independent Republican editorial posed this question on June 16, 1859, after a fugitive slave arrived in Chester. “After examining him and secreting him until dark,” the editorial went, some local people “raised some money, bought him a ticket to Elmira, and giving him a letter to Rev. Mr. Beecher, of that city, they put him aboard of the New York and Erie [railroad] cars bound westward.” The paper warned against violating the Fugitive Slave Act, which made it the duty of all officials to assist in the capture of runaway slaves, or any law they might disagree with: “Soon, very soon, will not only this fair fabric of Republican Government, reared at so great a cost by our fore-fathers, fall and go to ruins.” The next week a rival paper, the Goshen Democrat, ran a counter-editorial calling slavery “a crime against nature and against God”: “We will...venture to inform our neighbor, that there is an underground railroad in this (and many another) County, and all the dough-faced 'patriots’ in the Union can’t tear it up.” Some people in Orange County, black and white, put themselves at great risk to help fugitive slaves. Their homes, and the paths that fugitives followed to Canada and freedom, comprised the Underground Railroad. Chester was an important railway hub. From there, fugitives could travel north by train or over land. It is difficult to verify local accounts of the Underground Railroad. No one who helped the fugitives escape talked at the time about what they did. But one first-person account was published in 1885, and reputable historians have taken up the subject. According to Helen Predmore, who wrote “The Chester (N.Y.) Church: A History 1799-1965,” some routes extended from Pennsylvania north through New Jersey “and across the Town of Warwick to Walton Lake and then into Chester, where two lines continued northward.” The home of John Milton Bull, at the north end of Walton Lake, was one stop. Bull used a carriage with curtains to bring runaways to Chester. According to Predmore, Bull would drive the fugitives into the Presbyterian parsonage barn of the Rev. James W. Wood, on the southwest corner of Hambletonian and High Street. They were brought into the house under cover of darkness. Goshen pediatrician Dr. James Wapshire lived in the house from 1964 to 1984. He said that he and his brother as children discovered a hollow sound to the wall behind a built-in bookcase next to the fireplace. Investigating further, they found a removable bottom back panel and, behind that, a cavity in which a person could stand. The basement yielded another surprise. One day the Wapshires’ caretaker, who lived across High Street near the present-day 911 call center, surprised Dr. Wapshire’s mother by suddenly appearing in her kitchen. He had come through a tunnel connecting his property to the Wapshires’ basement and then made his way upstairs. The caretaker’s home was later demolished. The apparent exit in the Wapshires’ basement looks like a window, but it is below grade level. It was subsequently blocked off and painted. Its current residents know nothing of its history. Was this tunnel used by fugitives to enter the caretaker’s house, which is closer to the railroad? Dodging the marshal in Goshen Although not as important a stop as Chester, Goshen also played a role in the Underground Railroad. Ambrose Spencer Murray, director of the New York and Erie Railroad from 1853 through 1867, lived in Goshen and was a staunch abolitionist. He was said to have left tickets and passes expressly for fugitives at the Erie station. When federal marshals and slave owners were searching for escaped slaves in Chester, the fugitives might be put off on a side track at Goshen, or cross the tracks to the Vail Brothers dry goods store on West Main Street (across from the Occidental Hotel, which was near the present-day post office). They could hide among the boxes and barrels in the basement before continuing their journey. If pursued, they could escape by a side door. An African-American from Goshen, Matthias Droyer, purportedly assisted store owners Wilmot M. and Robert Montgomery Vail in their efforts. Dr. Graham, whose dentist’s office was above the Vails’ store, also helped. In the June 11, 1885, edition of The Orange County Farmer, Wilmot described the plight of an African-American family with two children who arrived at his store closely pursued by their slave owner and a federal marshal. With the help of Dr. Graham and local black citizens, Wilmot managed to outwit and ultimately intimidate the pursuers, according to his account. He said many Goshenites were privately anti-slavery. “I have known lots of Democrats who pretended to be firm friends of slavery in those days, but they never refused to contribute in a single instance towards a fund to help some poor devil of a runaway to freedom, when asked,” Wilmot wrote. “They practiced better than they preached.” Thanks to a few brave souls, Orange County can claim some moments of grace in the history of slavery in the United States. The split in sentiment in the Democratic Party helped the anti-slavery Republican Party in 1860 elect a little-known moderate to the presidency: Abraham Lincoln. Slavery, and whether it would be allowed to continue, was the central cause of the bloody war to come.

Terrified family finds protection

This account by Wilmot Vail was first published in The Orange County Farmer in 1885. Sue Gardner, local history librarian at Albert Wisner Public Library and archivist for the Historical Society of the Town of Warwick, transcribed a 1909 newspaper clipping now in the collection of the Town of Warwick Historical Collection and reprinted here. I enlisted in the cause in 1847 when living at Goshen at the age of 19 years, and I was the recognized “agent” of the system at that station...Sometimes fugitives arrived on foot and sometimes a friendly conductor of a railroad would help them on their way. At Newburgh there was a colored man named Alsdorf, of a family of musicians, who provided for and concealed fugitives until an opportunity came to send them north....I had a friend named Coddington, an abolitionist and Erie Railroad conductor, who carried many fugitives on his train westward to Buffalo on tickets given to me for the purpose by Hon. Ambrose S. Murray, of Goshen, who was a director of the railroad, bank president, and represented his district in Congress. These tickets were especially marked. If the part y was closely pursued by his owner and a U.S. Marshal, we sent him in the opposite of Newburgh....

I never experienced any trouble in securing funds for the cause and I found men of both political parties equally ready to contribute. Among those who backed me was “Bill” Rumsey, a Goshen man, who kept in the background....Another of my secret backers was a dentist who rented a room over my store, named Graham. He was president of the Democratic club, and was above suspicion.

There were many interesting incidents that occurred...The most pathetic one was a sudden appearance in my store of a fugitive slave, with his wife and two children, one an infant borne in its mother’s arms. Their scared and appealing look I shall never forget. The man handed me a slip of paper which had on it simply the word “Vail.” They said they were closely pursued. Knowing that no time must be lost I opened the trapdoor to my cellar and hurriedly sent them below. From the cellar a door opened to the outside of the building. I then pulled a knob which rang a bell in the dentist’s room. Graham understood the signal and rushed down in his shirt sleeves and I had not more than made him acquainted with the situation when in rushed a United States Marshal and the owner of the slaves. In the meantime, Graham had hurriedly obeyed the instructions I gave him, to go downstairs and get the fugitives out, which angered and disappointed in his prey escaping, [the marshall] said to me, “I want you.” “I suppose so,” I replied, “what do you want of me?” During this brief colloquy Graham had sized up the situation and passed the word among the colored population to rally in my defense. Within the space of ten minutes there were at least one hundred Negroes gathered in front of my premises ready for a fight. Things looked serious for the U.S. marshal when Graham came in and explained that he was the chairman of the Democratic club of Goshen.

He said, “Now look here, Vail hasn’t those people. I’m a Democrat. They went on the train that just went to Middletown.” That little speech saved us. The train was still standing at the depot and the marshal and slave driver jumped aboard and were carried off. In the meantime arrangements were made to get the fugitives out of town and the milk train came along and they were put aboard and taken to Newburgh and Alsdorf took them in charge. An hour later the marshal came back to Goshen furious over the trick that had been played and said to me, “We will take you anyway. You are under arrest. We will take you to Fort Lafayette.” It was then about dusk and observing the Goshen Negroes were standing on the corners ready for a fight, the marshal concluded it advisable to let me go, and that was the last of this episode.