Horace Pippin lived here

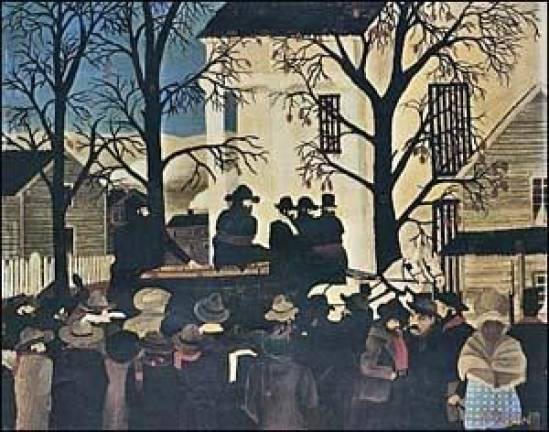

War, segregation, and ordinary life were themes of this great American artist Goshen Ask most people in Goshen who Horace Pippin was and, chances are, you’ll get a blank look. This lack of recognition is surprising, since this African-American artist grew up in Goshen. His works were included in private collections and museums all across the country, and one in Europe too. A veteran of World War I, Pippin overcame both a disabling handicap and racial prejudice to become a celebrated artist in the 1940s. His work is compared to Grandma Moses and Henri Rousseau. Critic Alain LeRoy Locke described him as “a real and rare genius, combining folk quality with artistic maturity so uniquely as almost to defy classification.” Pippin was born on Feb. 22, 1888 the year of the Great Blizzard in West Chester, Pa., and his family moved to Goshen three years later. His mother, Harriet, raised him in a house that still stands at 339 West Main Street. In those segregated days, Pippin attended the so-called “colored school” on Sayer Street, off West Main Street, which is now a private residence. As a child, Horace loved to draw. At around age ten, he entered a magazine art contest and won a box of paint, two brushes, and six colored pencils. He did some drawings for a fair at St. John’s A.U.M.P. (African United Methodist Protestant) Church. He cut circles out of fabric and fringed the edges, and on them drew bible scenes inspired by the stories he heard. Sometime later, Pippin recalled, the woman who bought them came up to him on the street and complained, “Those were some bum things.” She had washed them, and the pencil drawings disappeared. Horace had just finished 6th grade when his mother fell ill. He quit school to support the family. He worked briefly for a local farmer, Jim Gavin, and as a stable boy and coal wagon driver for Conklin and Cummins. He was a porter at the bustling St. Elmo Hotel in Goshen, on the site of the present-day post office. Pippin’s mother died in 1911. After 20 years in Goshen, Pippin left for New Jersey to find work. Wounded in war In 1917, he enlisted in the New York State 15th Infantry Regiment of the New York National Guard. Because of racism, he could not fight in an American unit, so he and his fellows were assigned to the French command. He and his unit, Co. K, now known as the 369th infantry, served on the front lines for six months without relief while under constant gas and shell attacks. Pippin wrote movingly of his war experiences and later painted “The End of War, Starting Home,” the most well-known of his war pictures. Only one of his diaries from the time survives, and is now in the Smithsonian. He writes about the day he was wounded: “Men laying all over wounded and dead, some was being carried. We wished we could help the wounded but we couldn’t. We had to leave them there and keep advancing, ducking from shell hole to shell hole all day .... The snipers were plentiful. I remember spotting a shell hole and made a run for it. Just as I was within three feet and getting ready to dive in, I were hit in the shoulder. There was four in the shell hole. One bound my wound the best he could and they all left me alone...” Pippin lay in that wet shell hole for a long time. Eventually a French soldier came along, but when Pippin tried to warn him about the sniper, the soldier fell down dead on top of him. Pippin had lost so much blood, he couldn’t even move him. Eventually other soldiers came by and shot the sniper. Pippin was placed on a stretcher and waited all day in the rain until doctors could attend him. His unit, the 369th, had never lost an inch of ground or had a man taken prisoner. Pippin and other members of his unit were awarded the Croix de Guerre. Another 27 years would pass before he was presented with the Purple Heart. Overcoming disability Sometime after this, he married Jennie Ora Featherstone Wade in West Chester, Pa. He was involved in church and civic activities, organized a Boy Scout troop, umpired baseball games, and served as the commander of a local black American Legion group. Pippin’s arm was partially paralyzed. He collected a disability pension of $22.50 a month. He discovered that he could draw by etching wood, which he supported on his knee, with a hot poker. Later, he taught himself to paint by supporting his weak working hand by holding it with the other. He used any paint he could find, including discarded house paint. Often, he would re-work the color, over and over again, until he had the shade he wanted. Pippin worked in obscurity for about eight years. In 1937, N.C. Wyeth, the famous artist, spotted one of his works in a shoe repair shop window, and helped arrange a one-person show of his work. Wyeth and Christian Brinton, a Philadelphia art critic, supported his career. Robert Carlen, a Philadelphia art dealer, sold his work. Pippin’s paintings were exhibited in New York and Philadelphia, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts. They were in demand by Hollywood celebrities, like Charles Laughton and Clifford Odets. The injustice of segregation was another of his major themes. In “John Brown Going to his Hanging,” the abolitionist sits in a wagon with his coffin as he is driven to his execution, surrounded by a mob. Some experts believe the lone black woman in front of the painting is his mother, who witnessed the event. The Goshen Public Library wrote to Pippin about showing his works there. In response, he painted “The Milkman of Goshen,” which was first shown at the Carnegie Institute Art Exhibition. It is the only painting that definitely depicts Goshen, although some experts say as many as seven paintings do so. His wife was committed to a mental hospital in 1946. Horace Pippin died in his sleep of a heart attack a few months later, followed two weeks later by Jennie. He is buried in Chester County, Pa. On April 24, 1998, Goshen celebrated “Horace Pippin Day” in a ceremony held at the 1841 courthouse. An historic marker was unveiled, later to be placed in front of St. John’s A.U.M.P. Church. The county historian, Ted Sly, has a videotape of the day’s presentation. Some local art teachers include Pippin in their coursework. To find out more about this extraordinary artist, visit the Goshen Public Library and Historical Society, which has books about Pippin. Photos of some of his paintings are above the shelves just outside the local history room.