Ice boats, 'faster than any motorcycle,' are part of Hudson history

In the early days of ice yachting, when iceboats were the fastest vehicles on earth and sailing them was a favorite sport of the rich, one name stands out: Jacob Buckout — a native of what is now Highland. Robert Wills, vice commodore of the Hudson River Ice Yacht Club, told the Buckout story at a recent program on the history of ice yachting on the Hudson, sponsored by the Town of Lloyd Historical Preservation Society in Highland.

Back in the 1880s, said Wills, the very best boats were made by Buckout. His workshop was in the part of Highland known then as Lewisburg, the narrow strip of flat land along the Hudson that is now under the Mid-Hudson Bridge. It was a perfect place to start a boat-building business, being right at the center of a 20-mile reach on the Hudson where ice yachts raced along the river and viewers congregated on the ice every winter. Wills added an extra tidbit: “That’s where all the betting took place.”

Although Buckout later moved his business to Poughkeepsie, the very heart of the iceboat racing world, Wills stressed the boat builder’s Highland beginnings. Buckout boats are still collected and maintained by individuals and clubs. The Hudson River Club owns several and still races them.

But ice yachting wasn’t always a sport. Wills explained that there were iceboats in the region as far back as the earliest Dutch settlements. Those boats were utilitarian vessels for moving goods in the winter. One early record of ice boats dates back to the Revolutionary War and involves a plan to blow up British ships on Lake Champlain. There’s also an 1812 record of using an iceboat to deliver people and sheep from Athens to Albany.

By the 1860s, however, the speed of iceboats had attracted the notice of wealthy sportsmen like John Aspinwall Roosevelt, Franklin D. Roosevelt’s uncle, and his friend, Archibald Rogers. Roosevelt and Rogers each had large fleets of the biggest and best ice boats in the world, adding new racing boats with the latest innovations every year.

“The two men traded world championships year after year,” Wills reported.

During the years of their friendly rivalry, they each won the coveted Ice Pennant of America four times.

Around 1860, ice yacht clubs began to form up and down the Hudson from Newburg to Athens. One of them, the Hudson River Ice Yacht Club, is still active today. Within the clubs in the early days, Wills revealed, there were many competing interests and much in-fighting, with clubs breaking off from each other. The Hudson River Club broke off from the Poughkeepsie Club, and the Hyde Park Club broke away from the Hudson River Club.

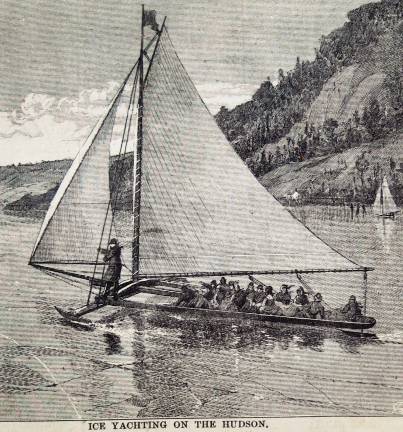

Illustrating his presentation with slides of historical ice yachts, Willis discussed the evolution of ice boat design over the years and described a number of famous iceboats. The early Dutch boats were regular soft-water boats, each with a runner plank attached along the boat’s bottom and runners — wooden shoes with cast iron skates on the bottom.

As iceboating became a sport, the design changed. Most changes were made with just one goal in mind — speed. Iceboat owners enjoyed racing the trains than ran along the river, and racing each other became organized sport. The biggest problem with the early recreational/racing boats was the sail design. The length of the boom and the placement of the mast put most of the propulsion at the back of the boat where there was less traction. This meant the boat spun out, of “flickered.” It was, Wills understated, “a little unstable.” Later improved sail designs minimized this problem.

Gilt and carvingsWills described a Buckout boat named Whiff, commissioned by Irving Grinell of Wappingers Falls. Whiff was exhibited at an 1876 Centennial Fair in Philadelphia. The cockpit was inlaid with spruce, walnut, and cherry. The bow strip was decorated with gilt, and a griffin was carved into the front. It had 300 square feet of sail and a 20-foot high mast. Whiff exemplified the ornamentation and expense of the boats ordered by the wealthy at that time.

Among the several iceboats that Wills described, he focused especially on two from the Roosevelt/Rogers glory days: John Roosevelt’s Icicle and Archie Rogers’ Jack Frost. The Icicle spent many years in the FDR Museum and now resides in the Maritime Museum in Kingston. Wills and his clubmates are hoping to get the state, which owns the boat, to allow them to restore it and recreate the historic World Championship races between the Icicle and the Jack Frost.

The Jack Frost has 750 square feet of sail and weighs 1,800 pounds. Based on a formula of one horsepower per square foot of sail, the Jack Frost is propelled by 750 horsepower. “I’ve been on it going 80 miles an hour” Wills said. “The Jack Frost accelerates faster than many motorcycles.”

Wills shared an Archie Rogers anecdote. “Archie was a daredevil,” he said. “He sailed where he shouldn’t have.” Once, out sailing with his wife near Hyde Park, the boat broke through the ice. Mrs. Rogers sent a telegram to their son: “Father and I broke through the ice today. All is well.” Wills has seen an old home movie of the mishap, with poor Mrs. Rogers making her way home in a soaking wet fur coat.

Franklin Roosevelt had a boat of his own — the Hawk, built by George Buckout, Jacob’s son, who took over the family business when his father died. The Hawk was given to Franklin by his mother when he was a young man. He enjoyed sailing it prior to contracting polio.

But for the most part, the advent of airplanes and automobiles dimmed the new generation of wealthy speed lovers’ enthusiasm for ice sailing. FDR eventually gave away many of the Roosevelt boats to people who worked on the estate. Wills is caretaker of an ice yacht named Kriss that belongs to the family of Arnold Brower, the son of a carpenter on the Roosevelt estate. The owners like to know the boat is well taken care of and is sailed on the river when conditions are right.

No longer exclusive to the wealthy, ice boating has become a different kind of sport with a different kind of boat. Modern boats can travel up to 140 miles an hour, and one day may even race in the Olympics.

For the traditionalists, the old ice yachts still have a place in the racing world. The Hudson River Club keeps challenging the Red Bank, NJ club, which has a tight hold on a trophy called the Van Nostrand Cup. The Cup was actually lost after a race in the 1800’s, then found in 1957 in the safe of a burned-out jewelry store. The Hudson River Club hasn’t won yet. But, Wills says, the after party is fun and they get to drink champagne out of the cup.

Ice boating on the Hudson is an increasingly fickle sport, with a limited number of days every few years when ice conditions allow it.

“When that happens,” said Wills, “we take the day off work.”