What If? The 'City of New Manhattan'

Governor Andrew Cuomo is fond of saying that the Second Avenue Subway, which opened earlier this year nearly a century after it was first proposed, is “proof that government can still get big things done.” The new subway line, Cuomo said, heralds “a new era in New York where there is no challenge too great, no project too grand.”

Naturally, the governor’s critics have been quick to dismiss Cuomo’s claims as self-serving and hyperbolic. And whatever one’s thoughts on the governor or the Second Avenue line, the critics have a point — the chutzpah required to build three new subway stops (in a city with over 400 others) doesn’t quite measure up to the ambition of the great civic undertakings of Manhattan’s past. Projects like the Brooklyn Bridge, which was the longest span in the world and the first bridge or its kind; or the Holland Tunnel — cursed and unappreciated by modern commuters, but a true engineering marvel of its time (ventilating the tunnel was deemed an impossibility before construction by none other than Thomas Edison).

Today, in an era in which even building a direct train line connecting Manhattan to LaGuardia Airport is a political impossibility, it seems reasonable to ask: do New Yorkers really think big anymore?

T. Kennard Thomson was not shy about dreaming up big things. Thomson, a well-regarded civil engineer in the early twentieth century, contributed to the construction of the upstate canal system and more than twenty of New York’s early skyscrapers. He is perhaps best remembered today, however, for his improbable plan, proposed in 1911 but as yet unrealized, to extend the island of Manhattan several miles south into New York Harbor, creating the “City of New Manhattan.”

Thomson detailed his plan in a 1916 Popular Science article. He begins, “At first glance, a project to reclaim fifty square miles of land from New York Bay, to add one hundred miles of new waterfront for docks, to fill in the East River, and to prepare New York for a population of twenty million, seems somewhat stupendous, does it not?”

Even a century later, stupendous seems to be an understatement. But despite the doubts of some contemporaries, Thomson was certain that the project was feasible, citing “the majority of engineers” and “hundreds of letters of encouragement.”

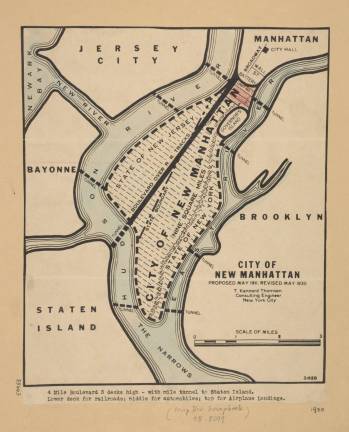

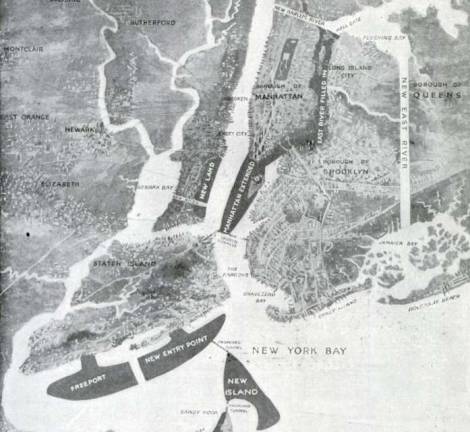

Thomson called on the city to build a network of coffer dams south of the Battery, which would be filled in to create newly habitable land. Governor’s Island, subsumed into the new landmass, would cease to exist as an island. New Manhattan’s new Battery would extend to within a mile of Staten Island, and the Staten Island ferry would be replaced by a “set of tubes and tunnels.”

Taxes on the new land, along with increased property tax revenue from increasingly valuable land on Staten Island, Thomson said, would help offset the immense expenses of the project, which he estimated would cost “a great deal more” than the then-recently completed Panama Canal. He wrote, “[T]he returns would quickly pay off the debt incurred, and then would commence to swell the city’s money bags, until New York would be the richest city in the world.”

Almost as a sidebar, the plan also calls for filling in the East River. “It would not be much harder to get to Brooklyn than to cross Broadway,” Thomson wrote. (Perhaps some of today’s L train commuters dreading the impending closure of the tunnel now wish they could walk from Williamsburg to Manhattan so easily.) Thomson makes no mention of what would have become of the Brooklyn, Manhattan, Williamsburg, and Queensboro Bridges, all of which were in operation by 1916, without a river to span.

With the old East River paved over, you’d need a new one, of course. So Thomson planned to dig a canal, “forty feet deep and one thousand feet wide, from Jamaica to Flushing Bay.”

Thomson presented his plan directly to Mayor William J. Gaynor in May 1911. The mayor’s response, if the current state of the Battery is any indication, was less than enthusiastic.

Undeterred, Thomson continued his efforts to build support over the next few decades. A map in the collection of the New York Public Library shows that by 1930 Thomson had significantly revised his plan. In the updated map, the plan to fill in the East River is abandoned, New Manhattan is bisected by a triple-decker boulevard (“Lower deck for railroads; middle for automobiles; top for Airplane Landings.”), and about half of the new land is labeled as part of New Jersey. In hindsight, selling New Yorkers on the idea that New Jersey would become part of Manhattan might have been the most politically impossible aspect of the entire scheme.

Alas, Thomson’s vision never became reality, and it’s probably for the best. Some ideas are too big for their own good. But his plan, fanciful as it is, has familiar features, fitting into the long history of New Yorkers rearranging Manhattan to suit their own purposes, imposing their will upon the natural landscape (Battery Park City and the FDR Drive are examples of the many pieces of the city built upon artificial land reclaimed from the rivers). It’s a reminder of what thinking big once looked like.